Antofagasta protest: “This dust is killing you” © Edgard Cross-Buchanan

The Escazu Agreement, the first treaty on protection of the environment in South America and the Carribean, and the world’s first to include protections for environmental human rights defenders, has been rejected as “inconvenient” by the Chilean government of Sebastian Piñera, which declined to ratify it on September 22, 2020.

The Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters has been signed by 24 countries and ratified by ten. To go into effect, the treaty requires ratification by 11 countries. Although Chile was an early champion, by rejecting the agreement at this late date, Chile ends its aspiration for environmental leadership according to Deutsche Welle.

Stemming from the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20), and championed by Chile and Costa Rica since 2014, the agreement was adopted at Escazú, Costa Rica, on 4 March 2018. The agreement had the support of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), and went through extensive negotiations, with significant participation of civil society and the wider public. The Escazu Agreement responds to the need for major advances on access to information, public participation and justice in environmental matters across the region.

“Above all, this treaty aims to combat inequality and discrimination and to guarantee the rights of every person to a healthy environment and to sustainable development,” says António Guterres in the foreword to the agreement. In his July 2020 brief analyzing the impact of COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean and addressing policy options and recommendations to face this situation, the UN Secretary-General highlighted the Escazú Agreement as “a valuable tool to seek people-centred solutions grounded in nature.”

Decision

Chile was the principal promoter and moderator of negotiations to develop the agreement together with Costa Rica, and yet the Chilean government reported to the parliament that “the signing of the Escazú Agreement is inconvenient given the ambiguity and broadness of its terms, its eventual self-enforcement and the mandatory nature of its regulations that would prevail over internal environmental legislation”.

The agreement establishes as its aim “the protection of the right of each person, of present and future generations, to live in a healthy environment.” The concept of “healthy”, says Chile’s Foreign Ministry, is widely disputed internationally and could conflict with the legal definition of the ‘right to live in a pollution-free environment’ that is contained in the Chilean Constitution.

Foreign affairs minister Andres Allamand stated to the press on 22nd September 2020 that Escazú would be “a treaty that violates Chilean legislation and gives the State and private interests uncertainty.” Because it “mixes human rights issues with the environment,” he added, Chile could face trials before an international Court.

Feedback

This decision has spawned a huge wave of criticism from the scientific community, civil society and academy as well as public figures such as the former president of Chile and member of The Elders, Ricardo Lagos, who called it “incomprehensible”.

“Chile loses credibility by not signing this agreement,” argues Paulina Astroza, an expert in international law and international relations who was invited to present her arguments in front of the Senate Environment commission.

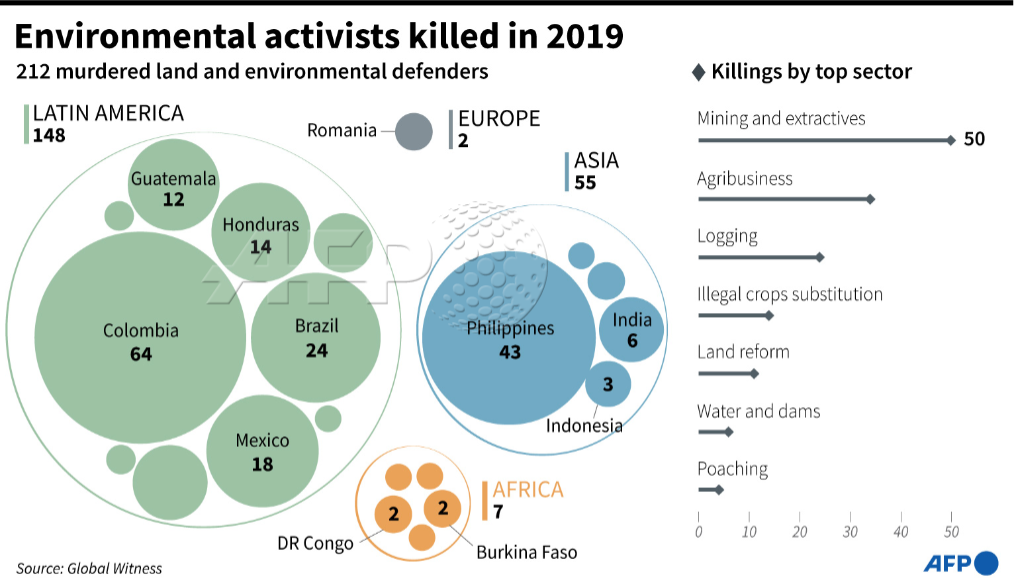

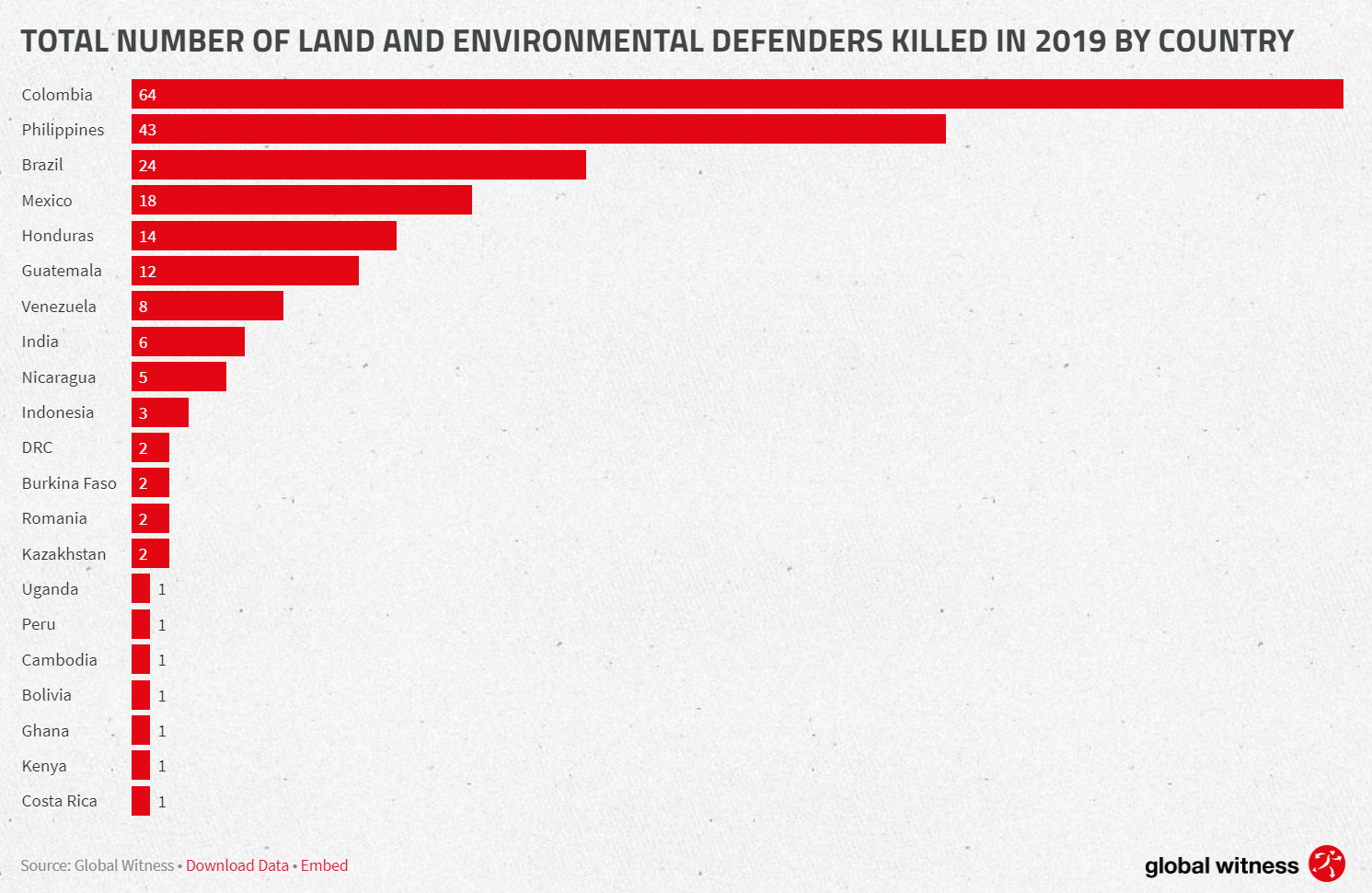

Furthermore, according to a new report from NGO Global Witness, a record 212 environmental defenders were killed during 2019. Seven of the top ten worst affected nations are in Latin America, where more than two thirds of total killings took place. The region has consistently been the worst affected since Global Witness started gathering data in 2012. The Chilean non-profit environmental legal organization FIMA produced a study comparing the Escazú Agreement and Chilean legislation. “In Chile, there is no recognition of human rights defenders in general, nor of environmental human rights defenders in particular (norms and policies), and there is no statute that allows knowing the rights they have to carry out their activities and to protect their physical and mental integrity,” it states.

Environmentalists emphasize the negative impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the protection of defenders in Latin America, which has created a context of growing vulnerability for them, and impunity for attacks on them.

Total number of land and environmental defenders killed in 2019 by country – Globalwitness

Although there have been important advances in the matter, the FIMA study concludes that there are still shortcomings that prevent citizens from fully enjoying access to information and environmental justice rights. For instance, the Escazu Agreement promotes access to information regarding the activities of private companies, such as the use of antibiotics in salmon farming, which is a major issue of public health in Chile. Also, the Chilean president and health minister are being formally accused by the Chilean Human Rights Commission for involuntary homicide and for falsifying public information about deaths from Covid-19 for political purposes, by manipulating the methodology of data collection, analysis and presentation.

Chile has seen growing environmental movements in its own “sacrifice areas” such as Quintero-Puchuncavi, where people have been subjected to ongoing episodes of widespread air pollution – to the point that regional hospital services collapsed due to the number of admission of cases of eye and skin irritation, nausea, dizziness, vomiting, and headaches. Scientific evidence of high public health risks, along with government policies that safeguard private interests have created an explosive atmosphere of distrust. Former minister of environment Marcelo Mena said: “It is essential to legitimize environmental processes and that people feel that business activities are not being carried out at the cost of their health”.

Indeed, economic development goals and the defense of private interests by the government continue to prevail over public health concerns in Chile. Citizens are being left with no control over their environments, and have to navigate between complex scientific reports on the health implications of industrial activities, the findings of independent journalists and the ambitious climate targets expressed by Chilean President Sebastián Piñera before the 75th general assembly of the United Nations. These targets are at odds with the president’s decision to not ratify the Escazu Agreement.

Prospects

On October 25th 2020, Chile is holding a referendum on the replacement of the current constitution. Both civil society and academia are actively discussing an ‘ecological constitution’ and many continue pushing for Chile to integrate regular citizen participation in democratic decision making in order to prevent socio-environmental conflicts. While there are high expectations around the new Chilean Constitution, signing and ratifying the Escazú Agreement would mean an important advance in the consecration of environmental rights and environmental democracy in Chile and throughout Latin America and the Carribean region. President Piñera must ratify the Escazu Agreement and live up to the words of someone who, in 2019, received a Global Citizen award.

In 1992’s Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, Principle 10 establishes that the best way to make environmental decisions is through the participation of all stakeholders. The Escazu Agreement is seen as a tool to consolidate this principle as a guarantee for citizens, consistent with the model that puts people at the center, and with protecting the ecological base that sustains development and social prosperity, thus avoiding many eco-social conflicts. Multilateralism is perceived as a means to tackle the climate crisis and future multidimensional challenges that stand before the world, where the competitiveness of economies should be measured by the increase in quality of life, inclusion and well-being that are provided in societies and their ecosystems.

The Escazu Agreement requires the ratification of eleven countries in the region for it to enter into force. So far there are ten countries that have completed this step, but another four are on that path: Colombia, Costa Rica, Peru and Mexico. Chile is within the group of 12 countries that have not yet ratified, together with Venezuela, El Salvador, Cuba, Honduras, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago.

And hopefully, Chileans will choose to ensure that a “healthy environment” is enshrined in a new constitution.

Milena Sergeeva

Global Climate and Health Liaison Officer for Latin America and the Carribean